I had no idea what to expect when I decided to head off to Nagaland for two weeks with my sister and her boyfriend visiting from England, my two year old son and five week old baby in tow. I’d heard amazing things about this remote area of North East India, a place further from my home in Mumbai than any place I’d been to before within India. I was further intrigued by the lack of online information available on Nagaland - with the exception of a couple of government owned tourism websites, and a handful of Trip Advisor reviews on accommodation in the region, it was as though Nagaland existed only in the imagination of the very few. Certainly no-one outside India had heard of it, and even Indians were hard pressed to identify the region.

Landing in Dimapur was a pleasant shock to the system. The airport is sweetly archaic, tiny but sufficient to handle the two flights a day which arrive from and depart to Kolkata. The city is dusty, crowded, but somehow exudes an immediate “gentler” vibe than the other Indian cities I’ve visited. We headed for the hills shortly after arriving, in a bid to cool ourselves down in more temperate altitudes. Nagaland has no rail system, and so the state relies on ancient creaking buses and taxis for transport – the latter usually Tata Sumos into which at least ten people can cram themselves and their baggage, making this a profitable business for the owners of the rickety vehicles. We were driven to Kohima by a schoolfriend of my husband, in a gesture typical of the generous and hospitable Nagas, he not only drove us from door to door, but arranged a wonderful lunch for us en route at a beautiful resort in the hills, and then left his car for us to use during our stay in Kohima.

As we left the smoggy confines of Dimapur, the air quickly became clean and fresh, the lack of pollution a welcome relief from Mumbai’s acrid atmosphere. Kohima is a sprawling city built around a large peak, its higgledy piggledy houses clinging for dear life to the steep sides, lining roads which wind round and round the hill. Walking is easier than driving around the city, though it’s exhausting on foot thanks to the steep inclines. We spent five days in and around Kohima, exploring the tiny markets with their exotic wares including several varieties of caterpillar which apparently make delicious snacks, and driving around the area thankfully in a four wheel drive vehicle, which gave us some respite from the poor roads which were ridden with potholes and often deep in mud. We drove deeper into the state, spending another few days in Mokokchung, another sweet town, similar to Kohima but smaller. Our friends in Mokokchung were perfect hosts, taking us to visit the small villages dotted around the area, many of which were chocolate box perfect, immaculately clean slices of rural bliss.

People all over Nagaland were warm, generous and friendly, their desire to help us driven entirely it seemed by genuine altruism rather than greed – this was evidenced by the fact that on several occasions, people tried to return tips to us, confused by the fact that we had paid them too much. When we explained again and again that the extra money was for the excellent service received, they invariably blushed and giggled, repeatedly trying to return the money. The Naga spirit of generosity is utterly genuine, and I wondered how far it would be corrupted once tourism hits the state. Nagaland is too far away from mainland India, too difficult to reach, and too challenging to traverse for most foreigners, and so it feels untouched, unspoilt by infrastructure which inevitably pops up to cater for the tourist scene.

We were treated like royalty everywhere we went, which was a tad disconcerting but heartwarming nonetheless. We were guests of honour at a society wedding, despite being inappropriately dressed, as we hadn’t exactly packed our finery. Nonetheless, we were picked up from our hotel by the Commissioner of Nagaland and his armed guards, and welcomed personally by him during his address to the congregation. We all blushed bright red as the wedding guests swivelled their heads to gawp at the “special guests from the Church of England”. We were also invited to address students from a local university who presumably didn’t get the chance to interact with real live Brits. Again, despite feeling like total fraudsters, we were made to feel like we were special, our young audience hanging on to our every word. It was a surreal but humbling experience.

Nothing in Nagaland feels like India. The people look different, their facial features closer to their Burmese neighbours, their language, food, culture and customs are as different from those of their Indian counterparts than from us Europeans. Our Naga friends talked of “mainland India” and “Indians”, and clearly do not feel part of the mother country. Their gentleness, genuine delight to give, with no intention of receiving, was a marked contrast with the more superficial hospitality in the more developed parts of India. Their tribal society has created not conflict, as one would expect, but rather harmony, with the 16 tribes co-existing in a mutually supportive manner.

Nagaland’s gentle exterior belies its troubled history – the region is notorious for insurgents and battles for independence since its creation in 1963 – before that, the area had been part of the state of Assam. It is not difficult to sympathise with a people who feel totally disconnected to their country, when they seem to have so little in common with the rest of its population. Right now peace prevails - hopefully this will remain and the Nagas will be granted their independence one day.

Monday, December 3, 2012

Friday, October 12, 2012

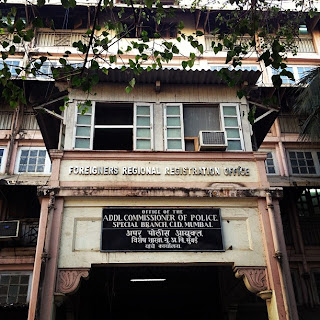

A visit to the FRRO (or - losing the will to live)

Once the initial surprise, shock and awe of Mumbai has worn off, all new arrivals into the city settle into the process of easing into daily life. The first major shock to the system comes in the form of the innocuously named FRRO - the Foreigners Regional Registration Office. Ask any expat who has been here for more than a few months about their experience with this spectacularly bureaucratic government body, and their response will range from the overtly angry - spitting with rage and fury, to a teary reminiscence, to a weary sigh filled shoulder shrug borne of final resignation.

The FRRO office is the place where every foreigner who comes to India on an employment or business visa must register, and the body which deals with all visa enquiries for long term foreign residents, or even those on tourist visas who may have inadvertently overstayed their visa. The process of dealing with the FRRO is somewhat similar to that of dealing with a death or news of a terminal disease – as the 5 stages of emotional reaction play themselves out – first denial, then anger, bargaining and depression and finally, acceptance. When I first arrived in India to work, I made the mistake of landing up at the FRRO two weeks after the stipulated 15 day timeframe for registration, so I went through all those 5 emotions in one sitting. For the average foreigner landing up at this innocuous looking office, the process generally goes as follows, over a number of visits or even in the space of a single morning : 1. Denial. On encountering the bureaucracy of the ladies in ugly sarees, the foreigner feels that they must all just be having a ‘bad day’, for surely no human being could ordinarily be this rude / curt / unhelpful / difficult and especially not en masse. This is India after all, people are known to be friendly and smiley here, and all Indians are by definition nice people. Plastering a big smile onto the face, and striving to keep the tone light and friendly, the foreigner bravely continues to try to explain the reason for the visit. As the documents which have been painstakingly collected together and copied as per the long list of requirements are scrutinized, and rejected one by one for irrational ‘irregularities’, the foreigner’s intention to smother the official with kindness and loving vibes slowly starts to transition to the surpressed rage which has been lurking not far below the surface.

Then comes the second stage as anger bursts out in staccato interventions “but all my documents are correct!” .. “but I checked the list twice!” “but I don’t have my bank statements from 5 years ago” .. no that IS the same signature” … and so on. This expression of anger is not only uncharacteristic behaviour for the typically buttoned up foreigner, but also has zero effect on the official who is busy throwing out painstaking collected documents. Realising that anger in this instance is futile, then comes the Foreigner’s attempt to bargain. Now bargaining and bribery, though alien to the foreigner, are part and parcel of the Indian experience, and expressed in a wonderful “one size fits all” descriptor – ‘jugaad’. This wonderfully evocative word means, according to Wikipedia, “a colloquial Hindi word that can mean an innovative fix, sometimes pejoratively used for solutions that bend rules, or a resource that can be used as such or a person who can solve a vexatious issue. It is used as much for enterprising street mechanics as for political fixers. In essence, it is a tribute to native genius, and lateral thinking”. “Jugaad” or “jugaad giri” (how to jugaad) is a simple word which summarises a way of life for an entire sub continent. Ever wondered why Indians all over the world are no 1 in any league table or industry you care to look at (with the exception perhaps of some notable sporting events)? Jugaad giri. Ever stopped to think about why in India, despite the chaos and the seemingly unmanageable bureaucracy, things just seem to happen? Jugaad giri. So Indians are very well versed at stretching and bending and manipulating the rules in the name of jugaad, but its an art you have to be born with. The hapless foreigner, when faced with a brick wall in the form of the FRRO officer, may resort to bargaining but it’s usually a sadly pathetic attempt to reason, cajole and / or beg. “If I get the signature redone by my office and bring it back will it be OK?” is met by stony silence. “but that’s a new rule and they didn’t tell me about it when I phoned” will be met by a blank look. And finally, “can I, er, um, er, pay something” is far too awkward an attempt to bribe, which will fall on deaf ears. Bargaining at the FRRO office will always result in disappointment, unless conducted by a true jugaad or one very very experienced in the art of when is a bribe not a bribe (and no, the FRRO does NOT accept bribes. Allegedly).

That brings me on to depression. Its not uncommon to exit the FRRO office feeling like you’ve lost the will to live. What started out as a seemingly straightforward, even innocuous task to get a visa stamp, has turned into a war of wills, a battle to end all battles, and an exhausting and seemingly never ending slide into a deep pit of bureaucracy, with all the cards seemingly stacked irreconcilably against you. Many foreigners stumble out of the office, glassy eyed and shell shocked. Along with the failure to have renewed the visa or been granted the magical ‘blue book” (the passport type book which allows you to reside in India), there comes the realisation that more paperwork is required (in triplicate) and yet more evidence needs to be submitted about one’s intentions for life in India. Some foreigners even give up in the face of this, and decide that India is simply not for them, booking the first plane back to civilisation and sanity. The majority however move on the next and final phase - Acceptance. This stage has more to do with a dulling of the senses, a feeling of helpless submission and final defeat at the hands of the senseless bureaucracy that characterises the FRRO experience than it does with finding inner peace or calm, but its Acceptance nonetheless.

A friend of mine recounts a particularly horrific experience at the hands of the FRRO – on showing up at the office for the compulsory registration process, the official in front of her took more than the usual painstakingly slow time to scrutinise her passport, looking for her entry stamp. When it became apparent that in fact there was no entry stamp in the passport and that the official at the immigration counter had overlooked this rather vital procedure she was told to ‘go back to the airport and get a stamp’. Now given the complexity of getting inside the airport with a valid ticket to travel, let alone trying to gain entry to get an entry stamp a week after entering the country is no task for the fainthearted. My friend managed to get inside and was not only asked which queue she had stood in (there are 20 odd lines at the immigration hall) but asked to identify the man who had failed to stamp her passport. Miraculously given that she had arrived a week earlier and at 2am, she managed to respond on both counts and there then began a pantomime farce which involved ALL the other immigration officials running after the ‘guilty’ party, pinning him down and tickling him (yes, really!), slapping him and throwing her passport at each other. Once the aforementioned stamp was in place, and a fat bribe taken, the passport was literally thrown in her direction, sailing right above her head to land on the extremely grubby floor. When she returned to the FRRO the following day, brandishing her entry stamp, the officials there could hardly believe their eyes. Apparently this ‘impossible’ task had been assigned to her to have her run in a wild goose chase before returning cap in hand to beg for the FRRO’s help. Unfortunately, my friend was far too smart and tenacious for the party poopers at the FRRO.

A wise friend gave me the following piece of advice when I first told him I was moving to India ; “don’t try and change India. Let it change you, but above all don’t try and change it. You’ll only go mad’. Truer words were never spoken. Surviving and learning to love India is all about the ability to embrace rather than criticise, to learn to love the craziness rather than be sucked under by it, to maintain a sense of calm detachment and rationale when all about you seem to be losing their heads. Take the FRRO. I’ve been visiting the same office for 9 years. Since I started going there on my annual pilgrimage to get my employment visa renewed, and then for my PIO card for me and then my newborn, I’ve seen the same faces working there, and have built up a relationship with them to the point where they raise an eyebrow when I sit in front of them to submit my (ever more complex) paperwork. I’ve even managed to crack a smile out of one of them. But, when I stopped and thought about WHY these government officers were SO very inflexible and so very difficult to deal with, I started to become aware of the frustrations which they themselves must be facing, day in and day out. Take the simple issue of money and the principle of fairness of distribution of wealth. Now each of these FRRO officers probably earns in the region of 4000-9000 rupees per month, if they’re lucky (USD$100-200). That money has to support an extended (joint family) of kids, uncles, aunties and aged parents. And they are made to scrutinise the tax returns and employment letters of foreigners who are earning say 200 times that per month ( a monthly salary of an expat in Mumbai will probably hit the one million rupees a month, or USD20,000. Even the ‘poorest’ expats will easily clear three or four times the monthly salary of these officials. So don’t you think they deserve to be cut just a little bit of slack? What can be worse than dealing with a bunch of whining foreigners day in and day out, who are trying to extend visas with incorrect paperwork, shouting and ranting incoherently and shoving their goddamned huge fat salaries in front of your nose, when you’re struggling to make ends meet, have a respectable if lowly paid job, you’re up at 4am to prepare breakfast for your extended family of in-laws and children and demanding husband, AND you’re also tired of saying the same thing to someone who you can hardly understand as they’re talking AT you and very fast. I kind of understand where these guys are coming from, at least when I’m in a more forgiving mood. Some of them clearly see their jobs as their own private vengeance against the days of the Raj, and yes that can be stressful, exhausting and frustrating but others are simply following their orders, and in India that means everything.

Sunday, August 12, 2012

Baking Queen!

In the past couple of years, I’ve rediscovered a latent love of baking which I didn’t even know I had in me. It has lain dormant for over twenty years, a subtle obsession planted deep in my soul since childhood which has only now re-emerged, thanks to a rush of hormones marking a particular lifestage.

Twelve years ago, I exchanged my fickle, twenty something life in London for a brief backpacker existence quickly followed by a smooth slide into the Expat world. During my twenties, I was too busy working eighteen hour days and attempting to climb the greasy pole of London’s competitive advertising circuit to worry about putting food on the table. I lived in a shared house, cooked my share of pasta dishes a couple of times a week, and relied heavily on Tesco’s variety of chilled “just like home made” pasta sauces which were brilliantly simplistic in their choice of red or white, spicy or mild, the overpriced versions from the chilled cabinet (for the couple of weeks after the salary arrived in the bank) or the cheaper options in packets, on the shelves (for the rest of the time). When the carbohydrate overload became too much, I simply switched to eating calorie controlled frozen dinners which cooked for sixty seconds in the microwave and which along with a few glasses of wine, just about curbed my hunger. I topped up my limited diet with a healthy expense account – after all this was the nineties and I had to keep my clients happy and well fed, and as expected, I dutifully maxed out my corporate credit card on five star dinners and lunches.

Moving to Asia meant a life of delicious, exotic food on tap. I discovered a world where domestic help came as a pre-requisite, a maid was standard issue for every expat, and they were all extremely capable of rustling up delicious, healthy, home cooked dishes which I’d discover in my fridge when I returned home from a day’s work. Failing that, if the maid was having a day off, for example, I’d stop off at one of the myriad street stalls to order Pad Thai or Chicken Satay, piping hot and laden with eye watering chillies which I theorised would kill off any bacteria. In ten years, I don’t think I managed to use my limited kitchen to cook much more than a slice of toast, and even that was an occasional deviation from the norm, given the poor quality of Asia’s bread (think plastic, sweet and sweaty). The fridge was for chilling beer and wine, the stove top was for the maid to produce her incredible curries and the kettle was for tea or for boiling water for a pot noodle.

When I met and married my husband, we made the most of Mumbai’s renowned service orientation, and I directed my new-found domestic goddess to organise a handy laminated file of takeaway menus. Our biggest decision of an evening was always – pizza, Chinese, Thai, or Indian. Or when we couldn’t be bothered, yesterday’s leftovers. It sounds sloppy, but it simply hadn’t occurred to me to bother cooking, and I used my poorly equipped kitchen, India’s lack of oven culture and its propensity to fry everything as excuses for my culinary lethargy. And then some English friends who were leaving Mumbai gave me their old oven, a tiny thing which could just about hold a (small) roast chicken but which aroused the first deeply buried twinges of domesticity within me.

I suddenly realised that I was sick of eating food whose ingredients had flirted briefly on a stovetop rather than meeting and fusing in a hot oven. This tiny addition to my kitchen ignited some deep part of my Englishness, and I became overwhelmed by the need to cook, and determined to overcome India’s limitations in that area. I discovered a tiny, smelly stall hidden at the back of one of the more popular market areas, and found that I could get surprisingly decent beef (or perhaps buffalo) there, as long as I was prepared to walk past stinking rows of live chickens lined up for the kill, and mangy flea ridden kittens slinking around in the hope of a handout. I found that I could source the cooking basics from the local shops, even occasionally find dusty imported items to top up my limited stores, and if all failed, I would simply carry critical ingredients back from my visits to the UK. I’d always made a trip to Tesco to fill my suitcase before leaving England, and now I simply exchanged boxes of wine and new shiny shoes for Yorkshire pudding mix, Bisto Beef gravy granules, goosefat for crisping roast potatoes, Colmans mustard, bacon and sausages.

I was all set to dive back into the world of cooking, and during that first year with my oven, I ran through the English classical recipe repertoire, producing beef roast dinners with all the trimmings, shepherds pies, toad in the hole,bangers and mash, beef and ale pies and lasagne (not strictly English, but close enough from the heavy carb and fat content perspective). My husband, who grew up in an English boarding school was delighted, reconnecting with his own inner schoolboy, and I called my expat friends home for Sunday dinner, delighting them with meals which were literally impossible to find in Mumbai, and stretching my tiny oven to its limit.

And then came the real double whammy – pregnancy combined with a brand new fitted kitchen, along with a shiny new “proper” fan oven. My inner domestic goddess returned with a vengeance, delighted to be finally liberated from the shackles of the wok and the instant noodle. As the pregnancy hormones kicked in, my repertoire expanded, and I developed a whole new obsession for cooking proper, old fashioned puddings and cakes. Victoria sponges, cupcakes, Lemon meringue pies, cheesecakes, queen of puddings, Banoffee pies, all came tumbling out of my new gleaming oven to the delight of my husband and the office, who became guinea pigs for my culinary experimentation. I realised then that this new found desire to create heavy, starchy delicious dishes was actually a throwback to the pre teenage me, and that the maternal cocktail of hormones swelling inside me had actually revived old memories of a childhood spent poring over floury cookbooks with my Mum who painstakingly taught me how to make pastry and cakes.

Now that I am pregnant for the second time, my baking obsession has intensified, and I find myself scouring the internet for new twists on old favourites. My husband loves the steady flow of delicious dishes which are emerging from that glorious oven, but he and I both know that once the baby is born, the desire to create complex fusions of fat and carbohydrate will be replaced by a fitness kick which will leave my oven cold and bare. I’ve promised him that I will fill the freezer before I deliver the baby, but it won’t quite be the same – those enticing baking aromas will no longer waft around the house and it will be back to Indian recipes and takeaways, at least until the next hormonal rush grabs me.

Twelve years ago, I exchanged my fickle, twenty something life in London for a brief backpacker existence quickly followed by a smooth slide into the Expat world. During my twenties, I was too busy working eighteen hour days and attempting to climb the greasy pole of London’s competitive advertising circuit to worry about putting food on the table. I lived in a shared house, cooked my share of pasta dishes a couple of times a week, and relied heavily on Tesco’s variety of chilled “just like home made” pasta sauces which were brilliantly simplistic in their choice of red or white, spicy or mild, the overpriced versions from the chilled cabinet (for the couple of weeks after the salary arrived in the bank) or the cheaper options in packets, on the shelves (for the rest of the time). When the carbohydrate overload became too much, I simply switched to eating calorie controlled frozen dinners which cooked for sixty seconds in the microwave and which along with a few glasses of wine, just about curbed my hunger. I topped up my limited diet with a healthy expense account – after all this was the nineties and I had to keep my clients happy and well fed, and as expected, I dutifully maxed out my corporate credit card on five star dinners and lunches.

Moving to Asia meant a life of delicious, exotic food on tap. I discovered a world where domestic help came as a pre-requisite, a maid was standard issue for every expat, and they were all extremely capable of rustling up delicious, healthy, home cooked dishes which I’d discover in my fridge when I returned home from a day’s work. Failing that, if the maid was having a day off, for example, I’d stop off at one of the myriad street stalls to order Pad Thai or Chicken Satay, piping hot and laden with eye watering chillies which I theorised would kill off any bacteria. In ten years, I don’t think I managed to use my limited kitchen to cook much more than a slice of toast, and even that was an occasional deviation from the norm, given the poor quality of Asia’s bread (think plastic, sweet and sweaty). The fridge was for chilling beer and wine, the stove top was for the maid to produce her incredible curries and the kettle was for tea or for boiling water for a pot noodle.

When I met and married my husband, we made the most of Mumbai’s renowned service orientation, and I directed my new-found domestic goddess to organise a handy laminated file of takeaway menus. Our biggest decision of an evening was always – pizza, Chinese, Thai, or Indian. Or when we couldn’t be bothered, yesterday’s leftovers. It sounds sloppy, but it simply hadn’t occurred to me to bother cooking, and I used my poorly equipped kitchen, India’s lack of oven culture and its propensity to fry everything as excuses for my culinary lethargy. And then some English friends who were leaving Mumbai gave me their old oven, a tiny thing which could just about hold a (small) roast chicken but which aroused the first deeply buried twinges of domesticity within me.

I suddenly realised that I was sick of eating food whose ingredients had flirted briefly on a stovetop rather than meeting and fusing in a hot oven. This tiny addition to my kitchen ignited some deep part of my Englishness, and I became overwhelmed by the need to cook, and determined to overcome India’s limitations in that area. I discovered a tiny, smelly stall hidden at the back of one of the more popular market areas, and found that I could get surprisingly decent beef (or perhaps buffalo) there, as long as I was prepared to walk past stinking rows of live chickens lined up for the kill, and mangy flea ridden kittens slinking around in the hope of a handout. I found that I could source the cooking basics from the local shops, even occasionally find dusty imported items to top up my limited stores, and if all failed, I would simply carry critical ingredients back from my visits to the UK. I’d always made a trip to Tesco to fill my suitcase before leaving England, and now I simply exchanged boxes of wine and new shiny shoes for Yorkshire pudding mix, Bisto Beef gravy granules, goosefat for crisping roast potatoes, Colmans mustard, bacon and sausages.

I was all set to dive back into the world of cooking, and during that first year with my oven, I ran through the English classical recipe repertoire, producing beef roast dinners with all the trimmings, shepherds pies, toad in the hole,bangers and mash, beef and ale pies and lasagne (not strictly English, but close enough from the heavy carb and fat content perspective). My husband, who grew up in an English boarding school was delighted, reconnecting with his own inner schoolboy, and I called my expat friends home for Sunday dinner, delighting them with meals which were literally impossible to find in Mumbai, and stretching my tiny oven to its limit.

And then came the real double whammy – pregnancy combined with a brand new fitted kitchen, along with a shiny new “proper” fan oven. My inner domestic goddess returned with a vengeance, delighted to be finally liberated from the shackles of the wok and the instant noodle. As the pregnancy hormones kicked in, my repertoire expanded, and I developed a whole new obsession for cooking proper, old fashioned puddings and cakes. Victoria sponges, cupcakes, Lemon meringue pies, cheesecakes, queen of puddings, Banoffee pies, all came tumbling out of my new gleaming oven to the delight of my husband and the office, who became guinea pigs for my culinary experimentation. I realised then that this new found desire to create heavy, starchy delicious dishes was actually a throwback to the pre teenage me, and that the maternal cocktail of hormones swelling inside me had actually revived old memories of a childhood spent poring over floury cookbooks with my Mum who painstakingly taught me how to make pastry and cakes.

Now that I am pregnant for the second time, my baking obsession has intensified, and I find myself scouring the internet for new twists on old favourites. My husband loves the steady flow of delicious dishes which are emerging from that glorious oven, but he and I both know that once the baby is born, the desire to create complex fusions of fat and carbohydrate will be replaced by a fitness kick which will leave my oven cold and bare. I’ve promised him that I will fill the freezer before I deliver the baby, but it won’t quite be the same – those enticing baking aromas will no longer waft around the house and it will be back to Indian recipes and takeaways, at least until the next hormonal rush grabs me.

Saturday, June 23, 2012

A peculiarly English obsession ...

England can be an utterly gorgeous place to be. The happiest, most positive space on earth, a country filled with possibility and opportunity, with smiles and great big surges of warmth. People connect, they reach out to one another and they spend hours together, whiling away the time and listening to each other’s stories.

Paradoxically, it can also be the worst spot on earth. A grey, depressing, bleak country, where people turn in upon themselves and barricade themselves into their homes. England can be a cold, soul destroying environment where even the simplest things seem impossible, and life appears to stretch endlessly into a vast chasm of future misery.

The truth is that my home country perpetually swings between these two extremes depending on one simple factor – the weather. Few other countries in the world are gripped so mercilessly by the weather gods than England – the fickle unpredictability of the climate means that nothing can be planned, that events can be ruined or made gloriously memorable depending on whether the sun decides to show its face or not and that as a result, we’re a nation obsessed by the weather barometer.

Most non Brits fail to understand our fixation with the weather. Those who live in more constant climates simply don’t get why we have to talk about it so obsessively and why it affects our lives the way it does. Essentially, it all comes down to a lack of control. Living in Mumbai, you know for sure that June to September will be wet and warm, October, March April and May will be fearsomely, blisteringly hot and humid, and November to February will be cooler and fresher, perfect months for planning outdoor parties, events and weddings. Though there are occasional surprises, when for example the temperature drops below 10 degrees celsius or when the Monsoon comes early or there’s a spatter of rain in February, but generally speaking the seasons are constant and wonderfully predictable. Mumbaikars plan their lives around the climate changes – some escape the monsoon rains for sunny European cities, others make the most of the few weeks of lush tropical landscapes which the annual downpour creates. Americans and even Parisians escape the searing summer months, and most of Southern Europe downs tools during the hot season.

England on the other hand is perpetually on the brink of indecision and arbitrary swings when it comes to the seasons. The newspapers are constantly full of headlines about snow in April, blistering heatwaves in September, and rain, always the rain, constant and about the only thing you can rely on to show its face when you least need it. England’s rain is not the warm, heavy raindrops of tropical climes. Nor is it a welcome spattering of coolness during an otherwise oppressive and sultry day. No, this kind of rain is random – it can appear suddenly even when you think the day will be bright and clear, and it can quickly turn nasty, with sheets of drizzle soaking everyone through to the bone, accompanied by a persistent wind chill which makes everything miserable. And with the rain comes the leaching of colour from the landscape, as bright hues make way for a palette of greys and muddy browns, and the country starts to scowl and eventually lose its collective temper.

Its not all bad of course. On the brief occasions where the weather is good and even great, the entire country joins in celebration, and a weird kind of camaraderie emerges, unheard of in England’s typically closed culture, where people normally shut themselves inside their houses and shy away from engaging with each other. Suddenly people are sharing spaces, crammed up against each other in parks, removing items of clothing and making casual, spontaneous conversation with strangers. And then, just when England seems on the brink of becoming a happier, more positive, friendlier country, the weather patterns shift, the sun disappears, and with it the atypical affability. Back comes the English reserve, and out come the umbrellas.

Mind you, on the rare occasions when the sun does decide to stick around, the childish delight in the warmth is soon replaced by a collective whining about the heat – we Brits generally weren’t made for warm weather, and somehow the average cool, grey climate suits our Eeyorish personalities. We need something to talk about, we crave something to bond our nation together, and that something is the weather. It’s a collective enemy which unites, and we generally prefer that its not too good to us, otherwise we lose the vital social glue of talking about the weather that we’ve come to rely on. Listen to any strangers conversing, or even on any groups of English people meeting or talking on the phone – it is virtually guaranteed that any conversation will either start with an opener about the weather, or meander on to the topic. We are a nation obsessed and in thrall to an unpredictability which those in the tropics or in perpetually cold countries don’t get. Its one of the things which makes us so sweetly eccentric I suppose, and its certainly one of the main reasons for my fleeing the country twelve years ago.

Paradoxically, it can also be the worst spot on earth. A grey, depressing, bleak country, where people turn in upon themselves and barricade themselves into their homes. England can be a cold, soul destroying environment where even the simplest things seem impossible, and life appears to stretch endlessly into a vast chasm of future misery.

The truth is that my home country perpetually swings between these two extremes depending on one simple factor – the weather. Few other countries in the world are gripped so mercilessly by the weather gods than England – the fickle unpredictability of the climate means that nothing can be planned, that events can be ruined or made gloriously memorable depending on whether the sun decides to show its face or not and that as a result, we’re a nation obsessed by the weather barometer.

Most non Brits fail to understand our fixation with the weather. Those who live in more constant climates simply don’t get why we have to talk about it so obsessively and why it affects our lives the way it does. Essentially, it all comes down to a lack of control. Living in Mumbai, you know for sure that June to September will be wet and warm, October, March April and May will be fearsomely, blisteringly hot and humid, and November to February will be cooler and fresher, perfect months for planning outdoor parties, events and weddings. Though there are occasional surprises, when for example the temperature drops below 10 degrees celsius or when the Monsoon comes early or there’s a spatter of rain in February, but generally speaking the seasons are constant and wonderfully predictable. Mumbaikars plan their lives around the climate changes – some escape the monsoon rains for sunny European cities, others make the most of the few weeks of lush tropical landscapes which the annual downpour creates. Americans and even Parisians escape the searing summer months, and most of Southern Europe downs tools during the hot season.

England on the other hand is perpetually on the brink of indecision and arbitrary swings when it comes to the seasons. The newspapers are constantly full of headlines about snow in April, blistering heatwaves in September, and rain, always the rain, constant and about the only thing you can rely on to show its face when you least need it. England’s rain is not the warm, heavy raindrops of tropical climes. Nor is it a welcome spattering of coolness during an otherwise oppressive and sultry day. No, this kind of rain is random – it can appear suddenly even when you think the day will be bright and clear, and it can quickly turn nasty, with sheets of drizzle soaking everyone through to the bone, accompanied by a persistent wind chill which makes everything miserable. And with the rain comes the leaching of colour from the landscape, as bright hues make way for a palette of greys and muddy browns, and the country starts to scowl and eventually lose its collective temper.

Its not all bad of course. On the brief occasions where the weather is good and even great, the entire country joins in celebration, and a weird kind of camaraderie emerges, unheard of in England’s typically closed culture, where people normally shut themselves inside their houses and shy away from engaging with each other. Suddenly people are sharing spaces, crammed up against each other in parks, removing items of clothing and making casual, spontaneous conversation with strangers. And then, just when England seems on the brink of becoming a happier, more positive, friendlier country, the weather patterns shift, the sun disappears, and with it the atypical affability. Back comes the English reserve, and out come the umbrellas.

Mind you, on the rare occasions when the sun does decide to stick around, the childish delight in the warmth is soon replaced by a collective whining about the heat – we Brits generally weren’t made for warm weather, and somehow the average cool, grey climate suits our Eeyorish personalities. We need something to talk about, we crave something to bond our nation together, and that something is the weather. It’s a collective enemy which unites, and we generally prefer that its not too good to us, otherwise we lose the vital social glue of talking about the weather that we’ve come to rely on. Listen to any strangers conversing, or even on any groups of English people meeting or talking on the phone – it is virtually guaranteed that any conversation will either start with an opener about the weather, or meander on to the topic. We are a nation obsessed and in thrall to an unpredictability which those in the tropics or in perpetually cold countries don’t get. Its one of the things which makes us so sweetly eccentric I suppose, and its certainly one of the main reasons for my fleeing the country twelve years ago.

Thursday, June 14, 2012

Canada's hidden depths

After a week in England’s pastoral Westcountry, which has slowly but surely soothed our frazzled nerves, our trip takes us to Canada. I’ve been here before, but as always, I’m amazed by the sprawling simplicity of this country. Somehow, it seems quietly uncomplicated, its wide, clean streets and huge boxy department stores a vast contrast from England’s higgledy piggledy streets where houses and shops squeeze together like a mouthful of crowded teeth. It is also possibly the absolute opposite of India – its calm, steady ambience diametrically opposed to a country which never seems to pause for breath.

We landed into Toronto Pearson Airport. The sun was shining, the sky was blue, and the entire place looked freshly scrubbed. The airport has free wifi which is instantly accessible without the need for passwords, laborious sign-in procedures or the exchange of cash, and to me this simple fact seems completely amazing. Mumbai has its own complicated wifi access which requires registration and passwords so that users can be monitored, and London wants your hard cash before allowing you to surf. The only slight blip on an otherwise peaceful entry was a grumpy immigration officer who asked us lots of surly questions, as if unable to believe our simple explanation that we were in Canada to visit friends and that we’d be leaving in a week. He scribbled on our immigration form in neon pink marker, and we were sent to a second stage of interrogation, during which we had to produce proof of our exiting flights and details of the professions of our hosts in Toronto. I wondered whether it had anything to do with the colour of my husband’s skin, but although the line contained a slightly higher percentage of Indians, overall there was enough white skin to suggest that this wasn’t simply about racial profiling.

Although I usually shun perfection and carefully sanitized environments preferring grittier cities with messy personalities, there’s something about Canada which I find very appealing. On the outside, it looks as bland as most of the US, but if you allow yourself to tune into the vibes which lie just below the surface, you’ll discover that a slightly more meaningful heart beats below its mild exterior. The US is all about being brash, opinionated and, dare I say it, arrogant. Most Americans actually revel in the fact that they don’t travel, considering their native country to contain everything they require for happy lives. As a result (and I am generalizing massively here to make a point, of course) the entire country, with the exception of New York and perhaps a few other random cities, has failed to temper its opinions with those of others, or allow the possibility of alternative thinking – and by alternative, I don’t mean the deliberately self-conscious embracing of Eastern philosophies, re-labelled by trendy West coast types. Perhaps because of this, Canada is quietly apologetic for its overbearing neighbour, its tourists and travellers proudly displaying its maple leaf flag to differentiate themselves from the nation that the world loves to hate. Canadians are known for their gentle demeanour, and they are just, generally, really nice people. They are helpful without being overbearing, interesting without being self-obsessed, perhaps because the policies and politics of the country are more about support and understanding than about ego and postulation. Maternity/parental leave is a jaw dropping year long (with 55% of salary paid), health care is publically funded and free, delivered according to need not ability to pay.

This is my third trip to Canada, and I’m struck once again by its sweetness and by its depth of character. If England is depressive and disapproving, and India is dramatic and expressive, then Canada is quietly cerebral and thoroughly unpretentious. If it wasn’t half a world away from Mumbai, then I could see myself here more often, if only to fuel my new found addiction to Tim Horton's French Vanilla cappuccino.

We landed into Toronto Pearson Airport. The sun was shining, the sky was blue, and the entire place looked freshly scrubbed. The airport has free wifi which is instantly accessible without the need for passwords, laborious sign-in procedures or the exchange of cash, and to me this simple fact seems completely amazing. Mumbai has its own complicated wifi access which requires registration and passwords so that users can be monitored, and London wants your hard cash before allowing you to surf. The only slight blip on an otherwise peaceful entry was a grumpy immigration officer who asked us lots of surly questions, as if unable to believe our simple explanation that we were in Canada to visit friends and that we’d be leaving in a week. He scribbled on our immigration form in neon pink marker, and we were sent to a second stage of interrogation, during which we had to produce proof of our exiting flights and details of the professions of our hosts in Toronto. I wondered whether it had anything to do with the colour of my husband’s skin, but although the line contained a slightly higher percentage of Indians, overall there was enough white skin to suggest that this wasn’t simply about racial profiling.

Although I usually shun perfection and carefully sanitized environments preferring grittier cities with messy personalities, there’s something about Canada which I find very appealing. On the outside, it looks as bland as most of the US, but if you allow yourself to tune into the vibes which lie just below the surface, you’ll discover that a slightly more meaningful heart beats below its mild exterior. The US is all about being brash, opinionated and, dare I say it, arrogant. Most Americans actually revel in the fact that they don’t travel, considering their native country to contain everything they require for happy lives. As a result (and I am generalizing massively here to make a point, of course) the entire country, with the exception of New York and perhaps a few other random cities, has failed to temper its opinions with those of others, or allow the possibility of alternative thinking – and by alternative, I don’t mean the deliberately self-conscious embracing of Eastern philosophies, re-labelled by trendy West coast types. Perhaps because of this, Canada is quietly apologetic for its overbearing neighbour, its tourists and travellers proudly displaying its maple leaf flag to differentiate themselves from the nation that the world loves to hate. Canadians are known for their gentle demeanour, and they are just, generally, really nice people. They are helpful without being overbearing, interesting without being self-obsessed, perhaps because the policies and politics of the country are more about support and understanding than about ego and postulation. Maternity/parental leave is a jaw dropping year long (with 55% of salary paid), health care is publically funded and free, delivered according to need not ability to pay.

This is my third trip to Canada, and I’m struck once again by its sweetness and by its depth of character. If England is depressive and disapproving, and India is dramatic and expressive, then Canada is quietly cerebral and thoroughly unpretentious. If it wasn’t half a world away from Mumbai, then I could see myself here more often, if only to fuel my new found addiction to Tim Horton's French Vanilla cappuccino.

Saturday, June 2, 2012

From Mumbai to Cornwall ....

I’m in Cornwall, the extreme southwest bit of England which looks like the big toe of the country, poking gingerly out into the chilly English Channel. This is one of England’s most rural areas, with 23% of people over retirement age, and a predominantly white population – 99% of Cornwall’s inhabitants are “White British” according to Wikipedia. My brown husband sticks out like a lovely sore thumb, his long black hair and beard giving him a distinctive, exotic look in this vanilla world. Tiny, pretty towns are dotted between enormous swathes of pristine countryside, which though brutally susceptible to wintry wind chills, light up in the summer months under sunlight which warms the land for up to eighteen hours a day. People here are ridiculously friendly – it’s a place where time runs incredibly slowly, and no-one is in a rush. There’s no road rage, no fury with meandering tourists (Cornwall’s second biggest source of income is tourism, after agriculture) and no snapping at strangers. I asked the ticket lady at the train station what time the train would arrive. She went online, slowly and methodically, to tell me exactly where the train was currently, did a few sums in her head and then gave me an expected arrival time with the added bonus of informing me that I should move my car to the car park on the opposite side of the tiny station, so my husband, who I was meeting, wouldn’t have to carry his suitcase over the bridge. Contrast that with the hordes of people pushing and shoving at a Mumbai rail ticket window, or the surly, grumpy response of a typical London railworker and you know you’re not in Kansas any more.

There's something very strange about my surroundings. For a start, its almost silent, the only ambient sounds are the discreet tweeting of birds and the gentle trickle of fresh water. I'm used to noise, all around me, all of the time, created either by the throngs of people who constantly shove and push their way into each other's space, or by the general din and cacophony of a crowded city which believes that the only way to get ahead is to be loud. I’d also forgotten how clean the air can actually be in the English countryside. There’s no stench of diesel fumes billowing from vehicles which are hanging together by the proverbial thread. There are no smells of cooking, now that the morning’s bacon and eggs have receded into a happy memory and a pleasantly full stomach. There’s no smog, no fog and no dust. Only clear, clean air and a temperature which is just the right side of fresh. I take deep breaths and I can almost feel the unadulterated air cleaning out the debris of accumulated toxins from my lungs.

As we tucked into our loaded breakfast plates this morning, enjoying the full English Breakfast experience, my husband and I contemplated the view – ponies in the neighbouring field, chickens clucking around their heavy feet, bright green grass and a cerulean blue sky. “I can see us living somewhere like this” he said. “We’d go mad after a week” I told him. “We need the constant rush of the big city, and there’s nothing to do here once you’ve finished admiring the view over a few pints of local scrumpy cider”.

I know what I’m talking about. I spent my childhood and teenage years in the neighbouring county of Devon – an area with similarly rural qualities, yet an important step closer to London and thus slightly more connected. You can take a train to the Capital from my home-town of Exeter in two hours, if you’re lucky. Cornwall doubles the journey time, which makes London practically a foreign country for the Cornish, unless they happen to fall into the minority of Cornish millionaires who can afford to pop up to the metropolis in their helicopters for a spot of shopping. I was a bored, fractious teenager, desperate to escape the confines of a sleepy part of the world, and missing out (I thought) on the glamour and excitement of the big city. Perhaps that’s what drove me around the world in search of adventure, my eventual relocation to Mumbai a direct result of a misspent youth in a tranquil environment. What I do know is that Devon and Cornwall, though extremely pretty and wonderful to visit, are not places to settle in if you get a thrill out of a buzzy, restless big city chock full of ambition.

I wish someone had invented cars which could fly half way round the world in minutes. That way my husband and I could have our ideal solution – weekdays in the cut and thrust of Mumbai’s intoxicating dynamism, and weekends in our serene picture postcard perfect cottage in rural England. Until then, we’ll make the most of this holiday, the perfect break from the madness of a Mumbai which though addictive, saps energy levels after a while and leaves you fractious, short tempered and with frayed nerves.

There's something very strange about my surroundings. For a start, its almost silent, the only ambient sounds are the discreet tweeting of birds and the gentle trickle of fresh water. I'm used to noise, all around me, all of the time, created either by the throngs of people who constantly shove and push their way into each other's space, or by the general din and cacophony of a crowded city which believes that the only way to get ahead is to be loud. I’d also forgotten how clean the air can actually be in the English countryside. There’s no stench of diesel fumes billowing from vehicles which are hanging together by the proverbial thread. There are no smells of cooking, now that the morning’s bacon and eggs have receded into a happy memory and a pleasantly full stomach. There’s no smog, no fog and no dust. Only clear, clean air and a temperature which is just the right side of fresh. I take deep breaths and I can almost feel the unadulterated air cleaning out the debris of accumulated toxins from my lungs.

As we tucked into our loaded breakfast plates this morning, enjoying the full English Breakfast experience, my husband and I contemplated the view – ponies in the neighbouring field, chickens clucking around their heavy feet, bright green grass and a cerulean blue sky. “I can see us living somewhere like this” he said. “We’d go mad after a week” I told him. “We need the constant rush of the big city, and there’s nothing to do here once you’ve finished admiring the view over a few pints of local scrumpy cider”.

I know what I’m talking about. I spent my childhood and teenage years in the neighbouring county of Devon – an area with similarly rural qualities, yet an important step closer to London and thus slightly more connected. You can take a train to the Capital from my home-town of Exeter in two hours, if you’re lucky. Cornwall doubles the journey time, which makes London practically a foreign country for the Cornish, unless they happen to fall into the minority of Cornish millionaires who can afford to pop up to the metropolis in their helicopters for a spot of shopping. I was a bored, fractious teenager, desperate to escape the confines of a sleepy part of the world, and missing out (I thought) on the glamour and excitement of the big city. Perhaps that’s what drove me around the world in search of adventure, my eventual relocation to Mumbai a direct result of a misspent youth in a tranquil environment. What I do know is that Devon and Cornwall, though extremely pretty and wonderful to visit, are not places to settle in if you get a thrill out of a buzzy, restless big city chock full of ambition.

I wish someone had invented cars which could fly half way round the world in minutes. That way my husband and I could have our ideal solution – weekdays in the cut and thrust of Mumbai’s intoxicating dynamism, and weekends in our serene picture postcard perfect cottage in rural England. Until then, we’ll make the most of this holiday, the perfect break from the madness of a Mumbai which though addictive, saps energy levels after a while and leaves you fractious, short tempered and with frayed nerves.

Sunday, May 20, 2012

Singapore changes ....

I made a 5 day business trip to Singapore this week. Singapore used to feel like my second home, thanks to the fortnightly trips I used to make to visit my clients back in 2001-3. I would shuttle between Bangkok and Singapore as though I was travelling from North to South London, and I quickly got used to the extreme levels of hygiene, the odourless air and the neatness which contrasted radically with the grimy stench of most other Asian cities, and the manufactured appearance of its controlled environment. I enjoyed my trips here, ate vast amounts of delicious food but generally got bored of the perfection very quickly. However, on this trip, made after 5 years, I found that things had changed significantly.

Singapore is of course a city, a city-state and also a country, with a population of 5.1 million – roughly the same number of people who are crammed into the tiny tip of South Mumbai. Like India, it was colonized by the British, yet has taken a very different path in terms of its development. Whereas India was left struggling to reconcile the impact left by the British with the complexities of its own systems, people and culture, Singapore, under a succession of efficient and determined governments and of course a considerably smaller, more manageable population, grew exponentially in terms of its economic might and its infrastructure. There’s a lot of negative talk about that growth, which has ultimately been achieved by controlling the emerging economy’s citizens via a set of rigid rules, and by a firm education and a harsh capital punishment system.

There is a vast amount of evidence of that control – not only in the clean streets and the manicured foliage which lines them, but also in the behaviour and reactions of the locals. I wanted to change my hotel booking and leave a day earlier than planned. I informed the front desk of my schedule change on my arrival. Apparently I couldn’t just tell them that I wanted to check out early, I’d have to go online and make the change. The system wouldn’t allow me to amend my booking, so I called the booking centre, where I was robotically informed that it was hotel policy not to cancel bookings unless the cancellation was made 48 hours before arriving. But I hadn’t known then that I would need to cancel my last night’s stay, I argued. In fact, I said (melodramatically and somewhat dishonestly) I had been called back by my doctor for an emergency checkup because I’m 6 months pregnant. I piled on the emotional pressure, and then added a business motivation for good measure - I was on the lookout for a good mid priced hotel as we were setting up an office in Singapore (true) and though I wanted to use this particular hotel I wouldn’t be able to unless some flexibility were extended. All of this met with silence and the repetition of the fact that “Madam it is hotel policy”. I changed from pleading to anger. I told them that I’d blacklist the hotel, blog and tweet and Facebook and leave negative reviews on Trip Advisor. More silence. “Don’t tell me that its policy. Listen to what I am saying and respond according to my situation, please” I begged the robot. “Send mail to booking centre with your reasons” came the response. Eventually, and on the back of a long, flowery and passive aggressive e mail, my final night’s stay was cancelled. But boy was it hard work.

In India, I would probably have faced the same kind of stubborn refusal to deviate from policy, but I’d have spoken to the manager and probably the emotional pressure would have done it. Singaporeans are literally unable to think outside the box. Unlike Indians who are resourceful lateral thinkers who will use ingenious methods to achieve their results, Singaporeans have been taught not to question authority, not to deviate from process, not to question policy. It was an infuriating insight into a country’s psyche. And next time, I’ll be more careful before I book.

I hadn’t been to Singapore for at least 5 years, and I was struck by the changes. What is still squeaky clean, shiny and flawless has been enhanced by a different undertone than I’ve encountered previously. Put simply, the energy of the city has changed. Not only are there more shiny buildings, towering edifices which soar over the city in what look like architecturally impossible shapes, but there is an entirely new undercurrent – of hope, possibility, success and dare I say it, creativity. I went for drinks with a friend on the freshly emerging Robertson Quay, lined with new watering holes and fancy restaurants, and walked back to my river facing hotel over a fancy pedestrianized bridge which was packed with small groups of local kids, sitting around bottles of hard liquor, drinking and being as rowdy as any drunken teenagers I’d seen on the streets of England, where drinking is a national pastime. They were loud, drunk and having a great time. I couldn’t reconcile this picture of unruly teens with the controlled, restricted Singapore which I’d come to expect. The bridge was lined with large green rubbish bins – according to my friend, the police had tried to crack down on this subversive behaviour initially by trying to move the kids away, and had eventually given up and decided that if they couldn’t ban underage drinking in public, they could at least ensure the place remained tidy. A bizarrely Singaporean resolution to a situation.

So the kids are rebelling, and no doubt Singapore’s art and creative scene will develop and grow and provide a much needed antidote to the suppression and the conformity as a result. One downside of this though is the emergence of a generational gap which has never before been seen – whereas previously, kids were subservient to the state and to their parents, now they are defying authority, and turning to themselves to create self sufficient groups. The concept of the family is under threat, so much so that the Singaporean government is apparently looking for strategies to rebuild communities and ensure that older people are looked after in their dotage, as has traditionally been the case, otherwise their care will require massive state handouts which the government cannot afford. These abandoned parents are now also taking on menial jobs to survive, and this is evidenced by the sheer number of older men and women driving taxis and working as public toilet attendants and serving in restaurants. When a rainy morning meant that I couldn’t get a taxi and was late for my meeting, a local friend explained to me that the majority of taxis are now driven by older people who get scared to drive in the rain, and so they simply stay off the streets when there’s a downpour.

I love Singapore’s new energy, and its clearly attracting others – multinationals are now focusing their regional hubs in the city and expats are flocking in. Procter & Gamble is moving its global headquarters from Cincinnati to Singapore, an unprecedented move which feels like a huge endorsement of Asia’s superiority in the global mix. That change is also driving prices up – the cost of living has already risen several times as foreigners flood into the city and the competition for apartments increases. It will be interesting to see how Singapore metamorphoses in the future. I for one am glad that its finding some kind of soul, the lack of which has always been my personal bugbear when it came to spending time there. I only hope that it manages to keep a balance, and that core values remain intact alongside the progressive change.

Singapore is of course a city, a city-state and also a country, with a population of 5.1 million – roughly the same number of people who are crammed into the tiny tip of South Mumbai. Like India, it was colonized by the British, yet has taken a very different path in terms of its development. Whereas India was left struggling to reconcile the impact left by the British with the complexities of its own systems, people and culture, Singapore, under a succession of efficient and determined governments and of course a considerably smaller, more manageable population, grew exponentially in terms of its economic might and its infrastructure. There’s a lot of negative talk about that growth, which has ultimately been achieved by controlling the emerging economy’s citizens via a set of rigid rules, and by a firm education and a harsh capital punishment system.

There is a vast amount of evidence of that control – not only in the clean streets and the manicured foliage which lines them, but also in the behaviour and reactions of the locals. I wanted to change my hotel booking and leave a day earlier than planned. I informed the front desk of my schedule change on my arrival. Apparently I couldn’t just tell them that I wanted to check out early, I’d have to go online and make the change. The system wouldn’t allow me to amend my booking, so I called the booking centre, where I was robotically informed that it was hotel policy not to cancel bookings unless the cancellation was made 48 hours before arriving. But I hadn’t known then that I would need to cancel my last night’s stay, I argued. In fact, I said (melodramatically and somewhat dishonestly) I had been called back by my doctor for an emergency checkup because I’m 6 months pregnant. I piled on the emotional pressure, and then added a business motivation for good measure - I was on the lookout for a good mid priced hotel as we were setting up an office in Singapore (true) and though I wanted to use this particular hotel I wouldn’t be able to unless some flexibility were extended. All of this met with silence and the repetition of the fact that “Madam it is hotel policy”. I changed from pleading to anger. I told them that I’d blacklist the hotel, blog and tweet and Facebook and leave negative reviews on Trip Advisor. More silence. “Don’t tell me that its policy. Listen to what I am saying and respond according to my situation, please” I begged the robot. “Send mail to booking centre with your reasons” came the response. Eventually, and on the back of a long, flowery and passive aggressive e mail, my final night’s stay was cancelled. But boy was it hard work.

In India, I would probably have faced the same kind of stubborn refusal to deviate from policy, but I’d have spoken to the manager and probably the emotional pressure would have done it. Singaporeans are literally unable to think outside the box. Unlike Indians who are resourceful lateral thinkers who will use ingenious methods to achieve their results, Singaporeans have been taught not to question authority, not to deviate from process, not to question policy. It was an infuriating insight into a country’s psyche. And next time, I’ll be more careful before I book.

I hadn’t been to Singapore for at least 5 years, and I was struck by the changes. What is still squeaky clean, shiny and flawless has been enhanced by a different undertone than I’ve encountered previously. Put simply, the energy of the city has changed. Not only are there more shiny buildings, towering edifices which soar over the city in what look like architecturally impossible shapes, but there is an entirely new undercurrent – of hope, possibility, success and dare I say it, creativity. I went for drinks with a friend on the freshly emerging Robertson Quay, lined with new watering holes and fancy restaurants, and walked back to my river facing hotel over a fancy pedestrianized bridge which was packed with small groups of local kids, sitting around bottles of hard liquor, drinking and being as rowdy as any drunken teenagers I’d seen on the streets of England, where drinking is a national pastime. They were loud, drunk and having a great time. I couldn’t reconcile this picture of unruly teens with the controlled, restricted Singapore which I’d come to expect. The bridge was lined with large green rubbish bins – according to my friend, the police had tried to crack down on this subversive behaviour initially by trying to move the kids away, and had eventually given up and decided that if they couldn’t ban underage drinking in public, they could at least ensure the place remained tidy. A bizarrely Singaporean resolution to a situation.

So the kids are rebelling, and no doubt Singapore’s art and creative scene will develop and grow and provide a much needed antidote to the suppression and the conformity as a result. One downside of this though is the emergence of a generational gap which has never before been seen – whereas previously, kids were subservient to the state and to their parents, now they are defying authority, and turning to themselves to create self sufficient groups. The concept of the family is under threat, so much so that the Singaporean government is apparently looking for strategies to rebuild communities and ensure that older people are looked after in their dotage, as has traditionally been the case, otherwise their care will require massive state handouts which the government cannot afford. These abandoned parents are now also taking on menial jobs to survive, and this is evidenced by the sheer number of older men and women driving taxis and working as public toilet attendants and serving in restaurants. When a rainy morning meant that I couldn’t get a taxi and was late for my meeting, a local friend explained to me that the majority of taxis are now driven by older people who get scared to drive in the rain, and so they simply stay off the streets when there’s a downpour.

I love Singapore’s new energy, and its clearly attracting others – multinationals are now focusing their regional hubs in the city and expats are flocking in. Procter & Gamble is moving its global headquarters from Cincinnati to Singapore, an unprecedented move which feels like a huge endorsement of Asia’s superiority in the global mix. That change is also driving prices up – the cost of living has already risen several times as foreigners flood into the city and the competition for apartments increases. It will be interesting to see how Singapore metamorphoses in the future. I for one am glad that its finding some kind of soul, the lack of which has always been my personal bugbear when it came to spending time there. I only hope that it manages to keep a balance, and that core values remain intact alongside the progressive change.

Thursday, February 23, 2012

Sort your basics, Gen Y

I’m sorry people. I’m probably going to piss you off and sound like your grandmother. And given that I’m in my fourth decade (just!) I suppose that you could arguably assume that I’m over the hill, disconnected, out of touch, practically a dinosaur, too geriatric to tweet, completely uncool etc. But I can’t keep quiet any longer about some basic stuff which is really just bugging me.

As a schoolgirl, when mobile phones were only seen frequenting the sets of Star Trek, and doing research meant a trek to a dusty library rather than the click of a mouse, I was taught “proper” grammar. I hated the endless repetition of tenses, the ancient teacher who it seemed hailed from a different era, the mind numbing dry subject matter which required discipline and endless patience to get right. Who cared about errant apostrophes or whether it should be whom instead of who? Why would I ever need this stuff? My spoken and written English was pretty good, life is short and I really couldn’t see the need for it.

As a result of my very proper, old school grammar training, I’ve become a bit of a grammar nazi, but you know what? I write well, and I sound intelligent when I put pen to paper. I can’t stand sloppy grammar and spelling, and whilst I appreciate that some people struggle with spelling, and others don’t learn English as a first language, the combination of a lack of attention to the rigours of correct grammar, as well as sheer laziness are contributing to a complete decline into slothful communication. Since when is it OK, ever, to write “wen” instead of “when”? “Plz” instead of “please”? “Da” instead of “the” and my particular personal irritant– “gud” or “cud” instead of “good” and “could”? I appreciate that this is the Twitter generation my friends, and that you have to work within 140 characters, very often .. but why not just write less, and at least make yourself appear less idiotic?

OK so fair enough, I’ll let you off the grammatically correct Tweets. Tweet away with your codespeak, (codspeak?). Go for it. But don’t send me resumes and covering letters for jobs filled with spelling and grammatical errors. And then wonder why I don’t call you for an interview. And please don’t post shit on my Facebook timeline that makes the grammar obsessive inside me cringe, and spoil my morning.

Whilst I’m at it I might as well air my second bone of contention. Why oh why can’t you people be on time? OK I appreciate that the inability to be anywhere at a specified time isn’t strictly a Gen Y affliction, but I really don’t accept that you can’t be on time for a meeting which starts at noon. And that potential job seekers think its OK to be late for an interview and that an under the breath mumbled “couldn’t find your office” will make it all OK. Googlemaps, people, Googlemaps. What could be easier? Especially as you can search on your lovely smartphones whilst you are literally standing on the street.

There ends my rant. I never thought I’d end up sounding like my mother. But you know what, I just think you Gen Y guys have it too easy. You expect everything, now, and you want to take the easiest route from point A to point B.

Now flame me, shame me, call me old. But at least my grammatical integrity is intact, and I’m never late for meetings.

Disclaimer : There are obvious exceptions to the above. But I’m making a point.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)